But Our Princess Is In Another Castle

Towards a ‘Close-Playing’ of Super Mario Bros.

*Originally presented at the Form, Culture, & Video Game Criticism conference on March 6th, 2004.

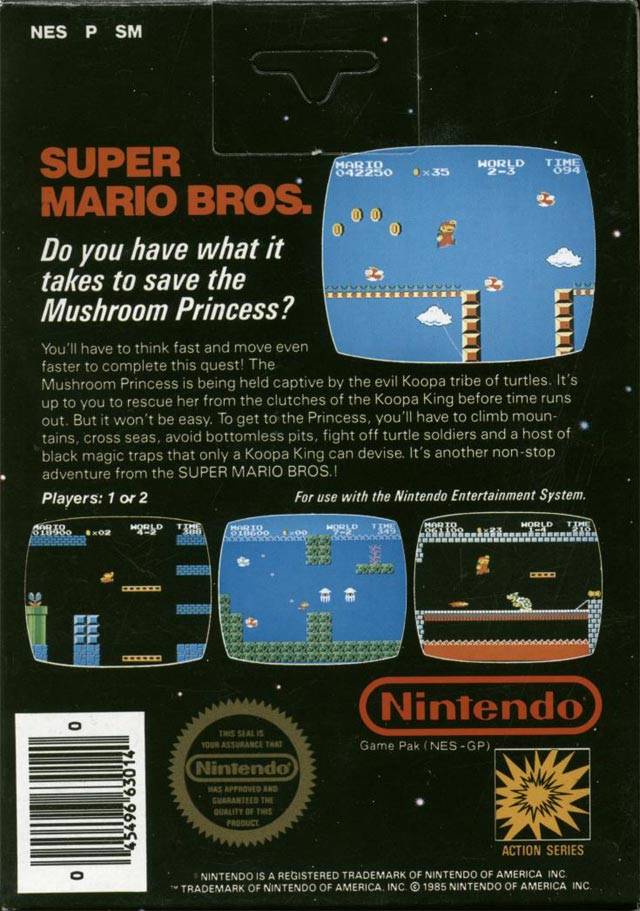

Do you have what it takes to save the Mushroom Princess?

You’ll have to think fast and move even faster to complete this quest! The Mushroom Princess is being held captive by the evil Koopa tribe of turtles. It’s up to you to rescue her from the clutches of the Koopa King before time runs out. But it won’t be easy. To get to the Princess, you’ll have to climb mountains, cross seas, avoid bottomless pits, fight off turtle soldiers and a host of black magic traps that only a Koopa King can devise. It’s another non-stop adventure from the SUPER MARIO BROS.!

What can this text from the back of the original Super Mario Bros. (1985) box reveal about the game awaiting play? Certainly, as a clever come-on to the would-be gamer, that first question – do you have what it takes? – just hangs in the air, demanding an answer. That ‘you’ will have to ‘think fast’ but ‘move even faster’ suggests some coordination of mind and body beyond conscious intention. You are limited by time, but the adventure is also ‘non-stop’. The present and future tenses both ensure the princess’s perpetual captivity and project the player’s repeated struggle. Saving her is always short-lived; it never achieves the completion of the past tense because the game has no memory. The title character, Mario, parenthetically qualified as the ‘hero of the story (maybe)’ by the instruction manual, is not even mentioned until the last line, and there it is not an adventure for the brothers but from them. As the repeated use of the second person indicates, it is you and not Mario who must save the princess. The two should not be confused, for you are not Mario, exactly. You have, or rather, are ‘what it takes’ to save the princess.

In the end, just what does it take to save a princess? What action activates that list of infinitives (to get, climb, cross, avoid, fight) and brings those heroics into real-time? Each image accompanying that text showcases Mario’s real power: jumping. The plumber who was once a carpenter was also known simply as ‘Jumpman’ back in the early eighties when his proto-princess, Pauline, tangled with the unreformed ape, Donkey Kong. In 2002’s Super Mario Sunshine, the latest sequel to 1985’s Super Mario Bros., the gameplay is still centered on Mario’s jumping ability, though this time augmented by a waterpack that allows the player to better control the height, length, and duration of his jump. In fact, every core Super Mario title has expanded on this power of the original Jumpman: from Super Mario Bros. 2’s choice of four different jumping styles to Super Mario Bros. 3’s and Super Mario World’s leaf and feather power-ups which allow for limited flight (the natural airborne extension of jumping) to Super Mario 64’s triple jump (the sound of a gleeful “Woohoo!” accompanying the third successful bounce).

So, it takes jumping prowess to save a princess. So, much of the carefully timed input communicated through two buttons, B and A, and a four-way directional pad translates into a good or bad series of jumps in the gameworld. So what? Any amount of actual play reveals statements like – “Mario is about jumping” – to be so obvious as to hardly need repeating. But it does need repeating, because though that single action defines Mario more than any other trait, such statements centered on gameplay are rarely heard in the small, but rapidly growing critical literature on videogames.

The way to begin to understand videogames is to look at actual videogames. Or rather, because equating seeing and knowing reinforces perceptual limitations, to play actual videogames. Though they share many traits with other media, their particular modes of play define videogame activity as much as acts of reading define literate activity. Close-readings remain a vital tool for literary criticism, and so I seek to perform a ‘close-playing’ of Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. (1985) as a gesture towards a theory of videogames built upon the analysis of individual games. Close-playing is not to be understood as the wholly immersive, nearly trancelike deep-play of hardcore gamers described by Sherry Turkle (1984), but neither can it remain on the surface, relying on some quick, cursory gloss of play mechanics. In most cases, close-play is a particular form of re-play, one that has grasped the ‘feel’ of the gameplay as a whole and then brings this to bear in local acts of interpretation, to those particularly suggestive moments or aspects of play that can reveal not meaning (not yet, at least) so much as the very experience of the game for the player.

The way to begin to understand videogames is to look at actual videogames. Or rather, because equating seeing and knowing reinforces perceptual limitations, to play actual videogames. Though they share many traits with other media, their particular modes of play define videogame activity as much as acts of reading define literate activity. Close-readings remain a vital tool for literary criticism, and so I seek to perform a ‘close-playing’ of Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. (1985) as a gesture towards a theory of videogames built upon the analysis of individual games. Close-playing is not to be understood as the wholly immersive, nearly trancelike deep-play of hardcore gamers described by Sherry Turkle (1984), but neither can it remain on the surface, relying on some quick, cursory gloss of play mechanics. In most cases, close-play is a particular form of re-play, one that has grasped the ‘feel’ of the gameplay as a whole and then brings this to bear in local acts of interpretation, to those particularly suggestive moments or aspects of play that can reveal not meaning (not yet, at least) so much as the very experience of the game for the player.

I don’t want to define this term – close-playing – too strictly; close-playings would be more apt, for the elements of play are so diverse in most games that each pass of a close-playing could only reasonably examine a discrete number of elements. Though I can imagine many alternate close-playings of Super Mario Bros. centered on iconography, genre conventions, the history of the series, the role of lead designer Shigeru Miyamoto, or a strict phenomenology, this close-playing will focus primarily on the uses of jumping as a unique, and fun, means of exploring its two-dimensional space.

Mario’s cultural ubiquity and historical significance, especially for game development, obscure the fact that it is the way his games play and not their narrative trappings that have captivated the minds (and hands) of gamers everywhere. One of the only serious analyses of the Super Mario series, Henry Jenkins and Mary Fuller’s “Nintendo and New World Travel Writing: a Dialogue” (1995), readily acknowledges that the chief pleasures of these games are not narrative and begins to move toward a consideration of gameplay. But given their postcolonial reading of the series (a bit of ‘theoretical imperialism’, to borrow Espen Aarseth’s phrase (1997)), they can only speak of some vague mastery of the “spectacular spaces” in the gameworld, not how such mastery is accomplished. This accords with Lev Manovich’s (2001) sense of the primacy of space as a new media type, though even his anaylysis of Doom and Myst fails to illuminate the differences in how that space can be traversed. In this sense, Jenkins and Fuller don’t take their reading of mastery far enough; the player does not strive to master the virtual space of the Mushroom Kingdom so much as he struggles to master himself and the hand-eye coordination central to successful exploration (or in Mario’s own terms – the jump).

Among its multiple aims, a close-playing seeks to understand just how digital space is traversed. This is why it seems so significant to me to state that Super Mario Bros. is about jumping, not saving the princess. The pleasures it offers are unique to the videogame medium. The gameplay requires neither strategic planning nor physical prowess but instead, some coordination of hand and eye in real-time (the ‘think fast and move even faster’ stipulation of the box). Its form of play is intuitive within minutes but does not clearly resemble any ‘real-life’ experience in translation, at least not in the way it is experienced. It requires no technical expertise but rewards practice and the development of unique skills. The graphics and sound suffice, but its brand of fun is completely bound to the gameplay – an unavoidable distinguishing factor for videogames as a medium.

In everyday life, jumping is both fun and potentially embarrassing. To jump is to test gravity’s pull viscerally, to feel your own weight as a physical object in space, to risk injury. But outside the confines of childhood (and even then, children must choose their jumps wisely in mixed company) and chasms being few and far between, there aren’t many contexts in which jumping is appropriate.

For Mario, jumping is the only appropriate, indeed possible, response to the strange Mushroom Kingdom he encounters. He must navigate space by going over, under, or skipping entire worlds (the fabled warp zones being the ultimate jump), but rarely can he go straight through. With his jump, he can attack from above and below, but even when he tries to shoot straight, his fireballs bounce. Only the invincibility star allows him unimpeded access, and how very different the game feels during those brief moments. If Mario masters the spectacular spaces of the Mushroom Kingdom, as Jenkins suggests, it is an awfully roundabout form of mastery.

Mario’s reliance on jumping becomes even clearer when compared to that of some of his videogame contemporaries. Mega Man and Simon Belmont of Castlevania, have low, leaden jumps that lead to much frustration, while Pit of Kid Icarus and Samus Aran of Metroid employ loose, floaty jumping that makes sense in their contexts (as a winged boy and low-gravity galactic bounty hunter) but lacks precision. Of course, those heroes begin their adventures with a peashooter, whip, bow & arrow, and arm cannon respectively, reminding us that they are not ‘about’ jumping in the way Super Mario Bros. is.

Mario’s jump also differs in purpose compared with his previous outings. In Donkey Kong, Jumpman only really needs to jump to avoid obstacles; this was jumping as evasion, always a response to direct threat, and a stiff response at that. This reason to jump is not lost in Super Mario Bros., but added to it is the impetus for exploratory jumping. The game’s push for exploration wouldn’t last very long if the player didn’t believe that there was something to explore, that something lay hidden beneath the surface of things. To provide incentive for this mode of jumping, the game-space is littered with hidden power-ups and secret paths, all quite necessary for a game of such length and difficulty. Rarely before 1985 had a game been so powerfully permeated with a sense of the hidden. The motivation to defeat the enemies and speed to the goalpost is consistently complicated by the desire to discover every last coin, invisible block, and secret area. A player will often face unnecessary dangers just for the chance to check out the site of a potential secret. In nearly every case, jumping is the means of discovery and, because of the danger, just as often the means of Mario’s death. In later levels, choices between exploring and pressing forward must be made on the fly, and because of time limit constraints, every victory carries with it the sense of undiscovered treasures left behind.

The discovery of secrets wouldn’t be so compelling if the means of discovery were not equally so. Jumping is inherently fun when the player has control over the speed, height, and direction of the jump with a high degree of precision. This is primarily a programming feat, but anyone playing Super Mario Bros. invariably reports that it ‘feels good’ or ‘plays well’. Its degree of responsiveness even allows the player to pull back mid-jump, and while not highly realistic in this regard, such robust control is a deep part of its pleasure. This flexibility and precision in jumping is put to particular use in the handling of enemies. No longer must Mario simply avoid his adversaries (though it is still an option, especially in handling the Koopa King ‘bosses’ at the end of each world); he can now jump on most, either squashing his foes or sending them skidding into each other.

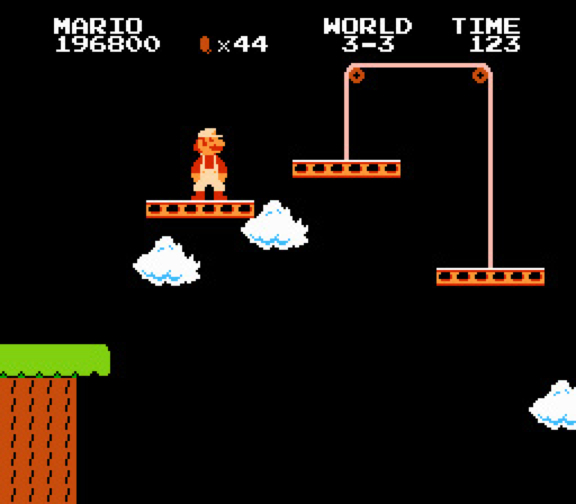

Jumping implies not only a minimum of two dimensions but a sense of gravity as well (and the less fun swimming sequences make it clear that some gravities are preferable to others). In order for the player to feel that Mario is a part of his environment, the plumber’s weight and impact must be felt. As with the player’s everyday experience of jumping, a sense of weight quickly grounds physical embodiment, and Mario’s various collisions with other moving bodies provide this sense quite well. The Goomba mushrooms satisfyingly squish, and the Koopa Troopa turtles hide in their shells; both encounters provide Mario a slight bounce. In other moments, the suspended platforms of the treetop levels act as veritable scales for the airborne plumber. The movement of the turtle shells when kicked provides a solid sense of the game’s physics; the player must constantly take these physics into account in order to avoid the unintentional ricochet of a shell or predict the bouncing arc of his fireball (a fact that makes the fireball a less precise weapon than the jump).

Jumping implies not only a minimum of two dimensions but a sense of gravity as well (and the less fun swimming sequences make it clear that some gravities are preferable to others). In order for the player to feel that Mario is a part of his environment, the plumber’s weight and impact must be felt. As with the player’s everyday experience of jumping, a sense of weight quickly grounds physical embodiment, and Mario’s various collisions with other moving bodies provide this sense quite well. The Goomba mushrooms satisfyingly squish, and the Koopa Troopa turtles hide in their shells; both encounters provide Mario a slight bounce. In other moments, the suspended platforms of the treetop levels act as veritable scales for the airborne plumber. The movement of the turtle shells when kicked provides a solid sense of the game’s physics; the player must constantly take these physics into account in order to avoid the unintentional ricochet of a shell or predict the bouncing arc of his fireball (a fact that makes the fireball a less precise weapon than the jump).

This simple yet consistent sense of physics in the gameworld contributes to the quality of emergent gameplay experienced in Super Mario Bros. Granted, its physics are not as sophisticated as those promised by the upcoming Half-Life 2, but they are quite a bit more complicated than the sun’s gravity in the primordial game, Computer Space. Combined with consistent, diverse enemy behaviors (part of a tradition encompassing both Pac-Man with its revolutionary ghost A.I. and Halo with its fiendish Elites) and a marked continuity of its scrolling gamespace, Super Mario Bros.’s physics lend that emergent sense that the game is never quite the same experience twice. The controlled yet inherently wild arc of Mario’s jump is the key element through which this emergence and its resulting fun are activated.

With this sense of the jump as the means through which play emerges, the severing of ‘you’ the player from Mario the character on the back of the game’s box begins to make more sense. James Newman’s excellent piece, “The Myth of the Ergodic Videogame: Some thoughts on player-character relationships in videogames,” (2002) disassociates player input from character:

Rather than “becoming” a particular character in the gameworld, seeing the world through their eyes, the player encounters the game by relating to everything within the gameworld simultaneously…Perhaps the manner in which the Super Mario player learns to think is better conceived as an irreducible complex of locations, scenarios and types of action.

The irreducibility and simultaneity of player-response suggest a complex relationship between player and machine that has yet to be adequately explored. With Mario, once the game begins the figure will simply stand there awaiting player input. His existence does not depend on the player, but because of time’s unstoppable countdown at the top of the screen, it is a doomed existence unless the player acts. (Later games present this split even more directly: In 1996’s Super Mario 64, Mario falls asleep if left unattended; similarly, in his 1991 debut rival Sonic the Hedgehog, that Futurist speed demon, turns to the player and taps his foot impatiently when denied his sensory input.) Thus, players become not Mario but those actions that will propel him across the game’s space in search of not only the princess, but more time and lives as well. Most significant of all Mario’s actions in this search, jumping is not what the player does – it’s what he is. As Sherry Turkle notes, “In pinball you act on the ball. In Pac-Man you are the mouth.” (1984, pg. 70) In Super Mario Bros. you are the jump.

The most accurate single word describing the experience of Super Mario Bros. is both intuitive and elusive: it’s fun. As Huizinga (1955, pg. 3) concludes at the outset of his examination of play in culture, “The fun of playing resists all analysis, all logical interpretation.” It is the fun that compels further play. This concept is not lost on anyone who was once a child, even if fun has no clear place in one’s adult life.

A man of society without games is one sunk in the zombie trance of automation. Art and games enable us to stand aside from the material pressures of routine and convention, observing and questioning…art, like games, became a mimetic echo of, and relief from, the old magic of total involvement. (McLuhan 1964, pg. 237-238)

But if videogames do not require ‘total involvement’, just what do they require? What kind of perceptual mode is being activated that would render sensible the statement: ‘you are the jump’ – particularly since this jump seems to lie at the heart of the fun? If close-playings are to prove fruitful, the player-critic must learn to use his ‘hand-eye’, that organic link in the man-machine feedback loop, in a more critical, self-aware way. With a nod to Vertov’s camera-eye, this hand-eye (and ear, for that matter) gestures toward embodying the camera gaze, moving from visual analysis to some fusion with the kinesthetic, as advocated by Newman. I see the hand-eye that knows itself, its own particular mediated status, as one of the central tools of a close-playing.

Already, in these first few decades of videogames history, games are beginning to make this reflexive, inward turn. The recent Gameboy Advance title Wario Ware, Inc.: Mega Microgame$! (starring a kind of inverted Mario) is one of the more recent instances of games taking on themselves as their own subject matter. As both mega – because it contains two hundred individual games, and micro – since each game is reduced to a ‘moment’ of only a few seconds, Wario Ware might more succinctly be subtitled ‘meta-games’. Commenting on both game forms and gameplay mechanics (timing, it turns out, is everything), it brings a self-consciousness to types of games often dismissed as simply relying on ‘twitch’ reflexes. Of course, anyone who has experienced the binary poetics of Ikaruga understands that thinking with your hands is a subtle and barely-understood art. But elucidating this art is one of the primary challenges for close-playings.

So, we must ‘think fast and move even faster,’ and understand this dance as we perform it. Is this coordinating ‘hand-eye’ a new perceptual mode or a remediation of other kinesthetic experiences? Close-playings seek to ‘feel’ such questions out, literally, and unveil what is obvious yet hidden in the very experience of normal gameplay. This will yield varying results depending on the game and may not lead to an immediate theory of videogames, but out of multiple (and no doubt competing) close-playings, perhaps some new critical understanding will emerge. In the meantime, close-playings must seek to articulate the experience of videogames through play (in both senses) while preserving both the strangeness and fun of that experience. The princess may yet remain in another castle. As it is for Mario at the end of world 8-4, the real reward in seeking her is the opportunity to jump again, through a new world, in a harder version of the game.

Bibliography:

Aarseth, Espen (1997) Cybertext: Perspective on Ergodic Literature, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bolter, Jay David & Grusin, Richard (1999) Remediation: Understanding New Media, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press

Huizinga, Johan (1955) Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture, Boston: Beacon Press

Jenkins, Henry & Fuller, Mary (1995) “Nintendo and New World Travel Writing: a Dialogue” in Cybersociety: Computer Mediated Communication and Community, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Manovich, Lev (2001) The Language of New Media, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press

McLuhan, Marshall (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press

Newman, James (2002) “The Myth of the Ergodic Videogame: Some thoughts on player-character relationships in videogames.” Game Studies 2(1). October 21, 2003 http://www.gamestudies.org/0102/newman/

Turkle, Sherry (1984) The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit, New York: Simon and Schuster

~ Tevis Thompson

Published January 15th, 2011

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.