Kirby and Texture

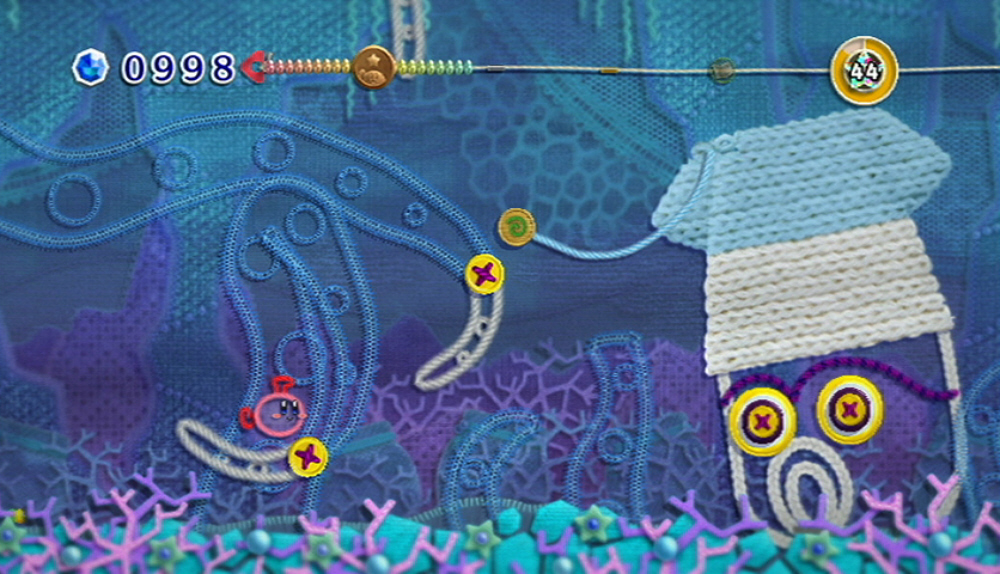

A few of the pleasures of Kirby’s Epic Yarn: becoming a bump behind the landscape curtain, the ropey water spilling forth from his firetruck hose, the way some ground just barely bends beneath his step.

A few of the pleasures of Kirby’s Epic Yarn: becoming a bump behind the landscape curtain, the ropey water spilling forth from his firetruck hose, the way some ground just barely bends beneath his step.

When I play this Kirby, my first of the series, I feel its texture. I feel it with my eyes. And this is what I return to, how a graphical style, a material concept can so determine my experience of a game.

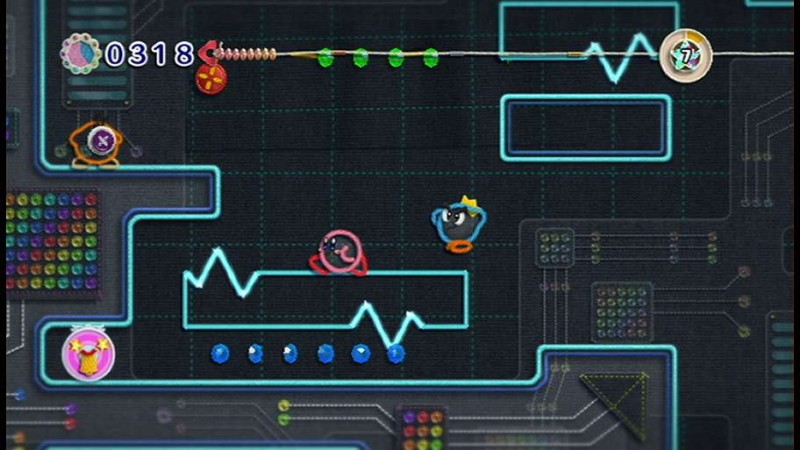

I play to explore the fabric of Kirby’s world. There is pleasure in simply seeing what comes next, how classic themes – a world of fire, of ice, of motherboards – will be reinterpreted according to its tactile logic. The darkness of a ghost manor as patched, moth-eaten blankets. The darkness of the denim cosmos punctured by buzzing buttons. Echoes of Méliès and the materiality of early cinema.

Most of Kirby’s Epic Yarn presents a shallow depth of field, a kind of thick 2D. There is little distance in the background, only layers of fabric; in fact, there is little distinction from the foreground at all. Everything is intimate, close enough to touch, though not quite.

Most of Kirby’s Epic Yarn presents a shallow depth of field, a kind of thick 2D. There is little distance in the background, only layers of fabric; in fact, there is little distinction from the foreground at all. Everything is intimate, close enough to touch, though not quite.

I am reminded of another play on dimensions in the Paper Mario series, but there it is the drawn quality of its images that underpin its paper-thin aesthetic. Kirby’s world, though, celebrates the constructed over the drawn, the object over the image. And not just any object – clothing: lived-in, cozy, everyday (“This grass feels like pants!”). This is the opposite of the slick sheen that coats so many other videogames. And it is this very texture and the presence it lends to Kirby’s world that I want to grasp.

But how can I feel, let alone grasp, this texture? The only thing in my hands is a plastic Wii-mote. And not even one in full revolutionary mode, but turned sideways for classic NES-style play.

How does it make sense to say that Kirby’s Epic Yarn is soft? Pliant. That it is beyond cute – it is gentle. The gameplay is forgiving, famously so, though this is not merely an issue of ease, but collision as well. The very touch of many classic videogames enemies is toxic, as if the mark of a true hero is the ability to master distance and remain untouchable until you are ready to pounce. But Kirby bounces off many hapless foes, not in some wild whiplash, but mildly, almost politely.

I feel all these things not only with my hands or my eyes, but with my hand-eye. I do not simply coordinate my senses – I conflate them. They loop, collude, and as a result I feel the visuals and see the tactility. Kirby’s Epic Yarn foregrounds the very synesthetic experience of videogames. I can’t account for exactly how my senses cross and activate each other while I play. Which is to say: I don’t yet understand the basic videogame experience.

I feel all these things not only with my hands or my eyes, but with my hand-eye. I do not simply coordinate my senses – I conflate them. They loop, collude, and as a result I feel the visuals and see the tactility. Kirby’s Epic Yarn foregrounds the very synesthetic experience of videogames. I can’t account for exactly how my senses cross and activate each other while I play. Which is to say: I don’t yet understand the basic videogame experience.

But Kirby makes me feel closer to knowing, to almost grasping this common experience. And not because its gameplay is particularly groundbreaking. It is solid, friendly, mostly unremarkable. In fact, the very classic feel of its platforming elements (wii-mote gyroscopic moments notwithstanding) draws me closer to the motions other games go through. Its pronounced synesthesia throws into starker relief the invisible contortions all games demand of my hand-eye.

Even further, Kirby’s own interactions with his environment do not simply serve as window dressing. When I yank down the fabric of a tree to climb higher or unzip a castle wall to reveal its shallow interior or patch the overworld and let loose the logic of the yarn, I feel as if I am seeing through to the inner workings of the world, wrinkling the very fabric of the universe.

Even further, Kirby’s own interactions with his environment do not simply serve as window dressing. When I yank down the fabric of a tree to climb higher or unzip a castle wall to reveal its shallow interior or patch the overworld and let loose the logic of the yarn, I feel as if I am seeing through to the inner workings of the world, wrinkling the very fabric of the universe.

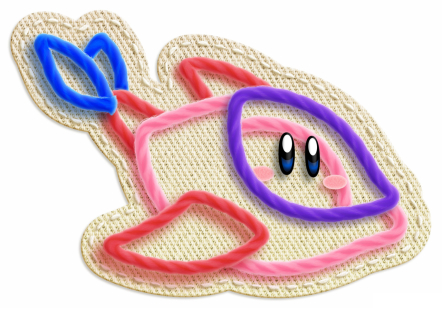

Kirby himself is only an outline, a figure made of lines and thus by definition two-dimensional. There can be no swallowing for Kirby this go-round, no consumption as usual, only a continual rethreading into different shapes and modes of play. He and his world are fabricated from yarn and the spool, household matter, things at hand. They’re reduced to base materials and stitched together with a DIY spirit that leaves the seams of the world exposed, and I feel as if his world, perhaps my own, might be finally comprehensible. It is the world at hand, a world I can almost grasp.

But there it is again, that impossible word: grasp. It is impossible to truly grasp Kirby and its virtual textures. And yet, this contradiction produces a distinctly pleasurable cognitive dissonance. Perhaps, in part, because the game intensifies, through its textile effects, those paradoxes of presence/absence, movement/stasis, touch/vision that exist in all videogames. The variety of game modes offered in Kirby extends the logic of the yarn to genres beyond the platformer: racing, surfing, even the arcade brawler (in tank blaster form). Specific games in videogame history are also referenced as Kirby is woven into a rocket (Galaga), digger (Dig Dug), dolphin (Ecco), firetruck (Mario Sunshine’s water nozzle), string in a maze (Pac-Man), star shooter (Kirby Super Star), and saucer (a possible nod to Kirby’s classic, and now missing, sucking ability). It’s no wonder one of the final unlockable levels, offering a frantic mix of these mini-games, is named Meta Melon Isle.

But there it is again, that impossible word: grasp. It is impossible to truly grasp Kirby and its virtual textures. And yet, this contradiction produces a distinctly pleasurable cognitive dissonance. Perhaps, in part, because the game intensifies, through its textile effects, those paradoxes of presence/absence, movement/stasis, touch/vision that exist in all videogames. The variety of game modes offered in Kirby extends the logic of the yarn to genres beyond the platformer: racing, surfing, even the arcade brawler (in tank blaster form). Specific games in videogame history are also referenced as Kirby is woven into a rocket (Galaga), digger (Dig Dug), dolphin (Ecco), firetruck (Mario Sunshine’s water nozzle), string in a maze (Pac-Man), star shooter (Kirby Super Star), and saucer (a possible nod to Kirby’s classic, and now missing, sucking ability). It’s no wonder one of the final unlockable levels, offering a frantic mix of these mini-games, is named Meta Melon Isle.

When I play Kirby in these alternate modes, old games almost seem suffused with a new presence, a denser substance. But even today’s most advanced control systems – the Wii MotionPlus, Kinect, and Playstation Move – can only track movement and provide audio-visual feedback, ever more precisely. Videogames themselves cannot push back. They cannot offer a reality of objects outside the self, those with weight, density, texture. This defines their virtual lack, this absent feeling of things. And yet Kirby’s untouchable textures remain pleasurable contradictions all the same.

It is to these pleasures I return. They linger, even as I think back on the game now. I peruse screenshots and ask myself again: why do they look SO PRETTY? They draw me nearer still; they ask me to caress and possess their precise fuzziness, their stitched edges, their knitted substance. I can already imagine a fully quilted, thoroughly unplayable recreation of Kirby’s Epic Yarn on BoingBoing. I’m not arts-and-craftsy myself, nor do I long for some pre-industrial past, and yet even I can grasp this desire for substance. It is not simply a creative impulse, to make things myself. The pleasures of disassembly and deconstruction course through Kirby too (unraveling Capamari’s snug little hat is a palpable delight).

It is to these pleasures I return. They linger, even as I think back on the game now. I peruse screenshots and ask myself again: why do they look SO PRETTY? They draw me nearer still; they ask me to caress and possess their precise fuzziness, their stitched edges, their knitted substance. I can already imagine a fully quilted, thoroughly unplayable recreation of Kirby’s Epic Yarn on BoingBoing. I’m not arts-and-craftsy myself, nor do I long for some pre-industrial past, and yet even I can grasp this desire for substance. It is not simply a creative impulse, to make things myself. The pleasures of disassembly and deconstruction course through Kirby too (unraveling Capamari’s snug little hat is a palpable delight).

When I consider the ultimate textural lack in videogames, I see that it does not indicate some underlying emptiness, some missing authenticity. It is but a function of our regular transactions with art and the imagination, with the virtual in everyday life. Whenever I long to lodge myself in the creepier corners of Kelly Link’s sentences, or comfort poor Walter White in Breaking Bad, or explore again the actual passages of my childhood home (not just the ghost house of my memory), I feel the pleasurable contradiction of my desires. I’ve grown so used to the impossible presences of art, to these material longings at play in my life – they’ve become practically invisible. Kirby and its texture make them, joyfully, visible again.

~ Tevis Thompson

Published February 5th, 2011

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.