Saving Zelda

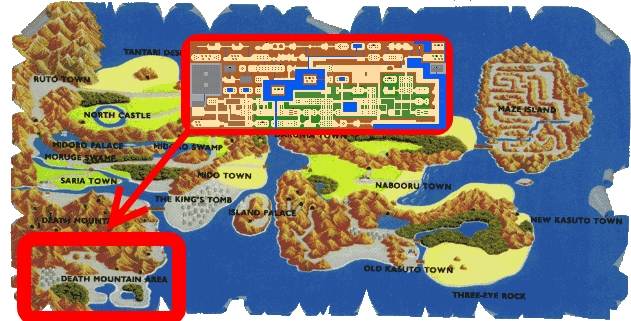

Late in the original Zelda’s second quest, I got stuck. I couldn’t find the relocated and very well-hidden eighth dungeon. Then one night I had a dream in which I took a map of Hyrule and drew large circles around the other seven dungeons. Somehow I had figured that dungeons were probably not right beside each other, and so by sectioning off portions of the map, I could better find the missing dungeon in the blank areas. I woke up, drew the circles, found the dungeon. Zelda possessed me, and in those pre-internet, pre-FAQ days, my mind worked on it even while I slept.

I still dream about videogames. Sometimes Mario, sometimes the latest Civilization, sometimes nightmares brought on by Demon’s Souls. But I don’t dream about Zelda anymore.

I’m a Zelda fan. The original captured my imagination in 1987 and hasn’t quite let go. I convinced my mother that Zelda II was so vital to my 11-year-old soul that she called, from Kentucky, a store in Canada to secure a copy. (This proved unnecessary, and that French version of the Adventure of Link ended up going to my cousin, Bear.) I’ve played every console Zelda through Skyward Sword, and I’ve even written fiction that takes Zelda (and Mario and Metroid) pretty seriously.

I’m still a Zelda fan today, but I’m not an apologist. Zelda sucks, and it has sucked for a long time. It’s not the greatest series in gaming, and Ocarina of Time is certainly not the greatest game of all time (it’s not even a great Zelda). The original Legend of Zelda is the greatest Zelda, Skyward Sword is the worst, and the trajectory is mostly downhill with a few exceptions (the bold horror of Majora’s Mask, the focused charm of Wind Waker).

But merely comparing Zeldas is of limited value. Sure, Zelda seems to occupy its own little pocket universe, but this doesn’t exempt it from comparison to its contemporaries. Game reviewers with expertise in a series seem particularly prone to these sorts of provincial arguments: Skyrim is a much-improved Oblivion! This does not mean it’s a good game. Skyward Sword being a fully actualized Wii Zelda doesn’t matter if Zelda itself is just a pleasant anachronism or, worse, fundamentally broken.

That is what I’m claiming: that modern Zeldas are broken at their core. By modern I mean the console Zeldas Ocarina forward (though Link to the Past is not innocent), and by core I mean their central structure and mechanics. I’m not going to harp on peripheral issues, though there are many that deserve mention. I’m not concerned with graphics, even if Wind Waker’s still-amazing style nearly saves it or Skyward Sword’s compromise between the painterly and the realistic is just that – a compromise, where nobody wins. I don’t think a modern game requires voice acting, although slow, repetitive dialogue boxes remain serious irritants.

I’m going to talk about the core of Zelda, its world, gameplay, difficulty, and story. Consider it an open letter to Nintendo, or at least my plea to the goddess. I want Zelda to be saved.

Everything That Is the Case

Why are there so many complaints about the initial thrill and then disappointment of Ocarina’s Hyrule field or Wind Waker’s ocean? Even the Lanayru desert in Skyward Sword offers a similar unfulfilled promise. The promise being: a world, vast, spread out before you, ripe for exploration, free. But when was the last time Zelda truly offered this? When the game plopped you in an open field and said: here is a world – have at it.

Modern Zeldas do not offer worlds. They offer elaborate contraptions reskinned with a nature theme, a giant nest of interconnected locks. A lock is not only something opened with a silver key. A grapple point is a lock; a hookshot is the key. A cracked rock wall is a lock; a bomb is the key. That wondrous array of items you collect is little more than a building manager’s jangly keyring.

Almost everything in Zelda has a discrete purpose, a tedious teleology. When it all snaps into place, some call this good design. I call it brittle, overdetermined, pale. It’s the work of a singleminded god, a world bled of wonder.

Players are constantly reminded that they’re shackled to a mechanistic land. There is no illusion of freedom because the gears that keep the player and Hyrule in lockstep are eminently legible. You read the landscape all too easily; you know what it’s asking of you. One of the greatest offenders occurred early on with A Link to the Past: most bomb-able walls became visible. What had been a potential site of mystery in the original Legend of Zelda (every rockface) became just another job for your trusty keyring. Insert here. Go on about your business.

It’s only gotten worse over the years. Skyward Sword, with its segregated, recycled areas and puzzly overworld dungeons, is not an outlier; it is the culmination of years of reducing the world to a series of bottlenecks, to a kiddie theme park (this is not an exaggeration: Lanayru Desert has a roller-coaster). But a world is not one predetermined sequence after another, and a world is not a puzzle with a single solution. A world is more than a space, more than a place; it is something to inhabit and be inhabited by. What you infuse a space with to make it habitable, to make it memorable (since memory is profoundly spatial), gives the place its character, its soul.

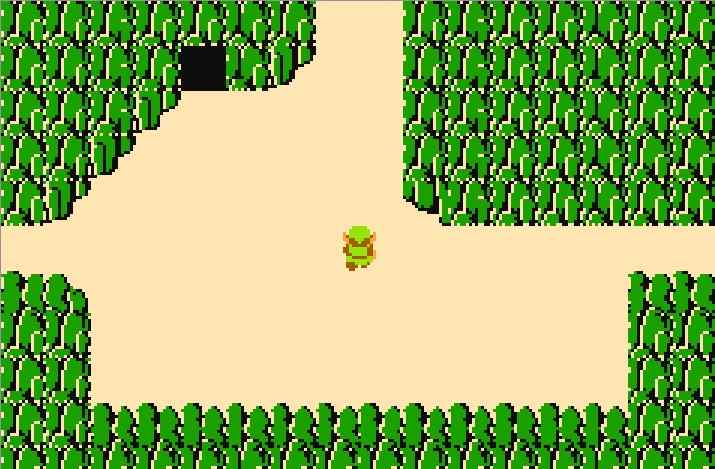

Tolkien knew this. His landscapes speak more convincingly than his characters. And Miyamoto knew this too. The apocryphal tale of his boyhood discovery of secret caves makes perfect sense when you play the original Zelda. That spirit of wonder, of potential secrets on every screen, permeated the map (and even the instruction booklet – it discreetly placed hints on the bottom of the page, inviting the player to pay attention because the hidden was everywhere). The rules of Hyrule were not at all clear to its first visitors, and one of the greatest pleasures came in intuiting the underlying logic (one secret per overworld screen, but almost one on every screen). The very existence of a second quest that remixed all the dungeons and all the secrets spoke of a world that was open and supple. The magic of the first Zelda was not locked down, given to a single iteration. It was its own sequel. It seemed like it could go on forever.

It did not. If Zelda is to reclaim any of the spirit that Miyamoto first invested in its world, it needs to do a few things. It needs to make most of the map accessible from the beginning. No artificial barriers to clumsily guide Link along a set course. Players know that game; they know when they’re being played. Link must be allowed to enter areas he’s not ready for. He must be allowed to be defeated, not blocked, by the world and its inhabitants.

This world, dangerous, demanding exploration, must also be mysterious. This means: illegible, at least at first. Zelda needs new unstated rules, ones that must be relearned, even by Zelda veterans like myself. How can you truly explore if you know how everything works already? How can you ever be surprised if every ‘secret’ is conspicuously marked as such? Hyrule needs space to breathe, fields of purposeless grandeur (like Shadow of the Colossus), where secrets could be anywhere because they’re not obviously right there. What is an adventure if not a journey through an unknown landscape? It’s not a retread across familiar ground, the car ride to work, the province of sleepwalkers.

Going Through the Motions

I know there’s something wrong with a game when it begins to feel like work. When it becomes predictable, rote, tedious. When I know what I’m supposed to do, but then I have to actually do it.

Zelda has felt like work since Ocarina, overstuffed with tasks, jobs, trials. And not just in the plodding opening sequences or all the requests by the feckless citizens of Hyrule. Even the sacrosanct Zelda dungeons, holiest of design holies, have fallen victim to this. So many things to do, so little pleasure in doing them. Dungeons suffer further in their over-reliance on environmental puzzles. Even calling them ‘puzzles’ does a disservice to all the fine puzzles in gaming. Most Zelda puzzles are tiresome and dull, but the problem isn’t just puzzle quality or lack of ingenuity; it’s using them as the structuring principle of a 30+ hour game. They determine the very flow of Link’s dungeoneering and make the whole plunge into the dark seem more like a modest exercise, a mock trial in which you needn’t break a sweat. Some claim the result is balanced, tastefully paced, well-appointed. So why do Zelda’s dungeons often feel so pedestrian and domesticated, with about the same rhythm and urgency as the music we call ‘adult contemporary’?

But wait, hasn’t Zelda always been like this? Aren’t puzzles somehow required by the Triforce? No, they are not. And it wasn’t always this way. The first two Zeldas had virtually no puzzles. You might have to push a block here or there, but the real test was finding your way through a maze and surviving. You had to keep track of where you were, explore every corner, and fight your ass off. In fact, mastering Link’s position on screen, in the game’s gridlike space, was key to fighting effectively. It was, and is, a surprisingly coherent, unified experience. It was, unapologetically, an action-adventure game. And a fuller, more complete experience in 1987 than anything Skyward Sword, and its magic stick, apes today.

A game that relies on puzzles, and Zelda in particular, is sometimes considered a ‘thinking man’s game’. Which is funny, because I haven’t had to think about much of anything in Zelda for years. This embarrassing prejudice against facility with a controller certainly isn’t doing Zelda any favors. We get instead a salad bar of limp riddles and the vague sensation that it’s good for us (kid-tested, mother-approved). Where is the joy in movement, the miracle of motion onscreen? We mostly just fumble with our keyring and call it a day.

It’s really a missed opportunity. Because clearly Zelda can offer compelling action when it wants to. Boss fights, when not overly puzzly, can still wow, and even standard enemies can engage on occasion. I still remember my first Stalfos battle in Ocarina. It felt like an actual encounter with real risk. But after a few repetitions, Stalfos became just another bundle of ticks to observe and exploit. The fighting in Wind Waker had potential too; Link was limber, his movements fluid. One of the greatest Zelda moments occurs when he ‘wakes’ the drowned castle and must fight hordes of Moblins and Darknuts simultaneously. The resulting chaos, and challenge, offers one of the few robustly emergent encounters in Zelda history. And yet, its rarity speaks again to all the untapped potential.

Skyward Sword would seem to respond to this – it’s even got sword in the title. But what a terrible, terrible response it is. I must give credit to Aonuma and his team for trying something new. But instead of dynamic, 1-to-1 motion controlled battles, we get fights that have been turned into puzzles. True, you can’t flail and succeed, but the supposed precision required actually just makes for a game of Simon Says. You go that way, I go this; you signal horizontal, I comply. Each motion is discrete, requested. (And that’s when the prickly Wii motion-plus actually works.) It creates a moment-to-moment pacing problem, inserting pauses, start-stop-repeat, and thus you rarely chain moves together with any sort of fluidity. Enemies are patient, almost polite, and usually allow for individual encounters, yet in a game about mastering a sword, you never even duel. When the mobs do finally come at the end, there is no finesse to be had. You will hack, and you will slash.

Basically, your skyward sword has no depth, never developing beyond the moves you learn at the beginning. And it lacks all robustness, proving as brittle as the rest of the world. There is, in fact, something brutish about Link and his whole grab bag of items, or rather, the way he switches between them. Controls for any single tool are generally manageable, but there is nothing graceful, or even coherent, in trying to string them together. It’s as if Nintendo thought the ‘adventure’ genre (which only Zelda seems to occupy) meant the player should be able to do just about anything. Want to shoot arrows, bowl bombs, blow sand, fly a beetle? Welcome to Zelda Party Resort, the mini-game gulag of champions.

We should’ve seen this coming. Zelda’s inevitable item creep started with a Link to the Past and has led to a Link-of-all-Trades. It’s only more pronounced now because of the mania for literally going through the motions, as if that’s what gamers have wanted all along. I don’t reject motion-control out of hand – I’m curious about all the possibilities of play. But when grafted onto Zelda, what becomes clear is that the series has lacked focus in its gameplay for a long time. Zelda simply has too many verbs. If the designers would choose just a few actions that Link could do very well (like moving) and coordinate them according to a common control scheme, then we might see Zelda achieve a true richness in its adventuring. It needn’t be as tight and utterly focused as Mario is with jumping, but it could at least be of a piece, compelling and consistent from the beginning.

Zelda has struggled with lucid, integrated gameplay since transitioning to 3D. Ocarina is lauded for taking Zelda into the third dimension, but I remain unconvinced. Modern Zeldas are translations of their 2D forbearers; they’ve never been fundamentally reconceived in 3D from the ground up. In choosing what elements made Zelda fundamentally Zelda, Nintendo chose poorly. They took the puzzles instead of the action, the conventions instead of the world, the items instead of the spirit. They never adequately considered the pacing differences inherent to 3D, the consequences of constantly looking around and recentering the screen, the changed expectations that attend a more recognizable world (not a compressed 2D gamespace). Unlike Mario, Zelda never convincingly made the jump. It’s no wonder Link still can’t.

Skyward Sword, the proclaimed future direction of the series, has only made this worse. It’s built upon so many layers of clumsy, sloggy protocol that it can’t possibly save the series with new features. Zelda needs subtraction, not addition. It’s not radical to suggest that Zelda fans would prefer a game that is elegant rather than convoluted. Fewer, deeper items and utterly overhauled but central swordplay would go a long way towards solving this. With such focus, Zelda might develop technique in its players, such that they actually improve as they play. As is, I can hardly claim to be much better at Zelda than I was after the first pitiless sequel. Not that I have to be.

Helicopter Parents

Zelda needs to be harder. Much harder. Not harder to solve, like Ocarina’s Water Temple, but harder to survive. The first two Zeldas were exquisitely difficult (the second excruciatingly so), and they were all the more wonderful for it. Thus, when I beat Link to the Past the first weekend I had it, after three years of waiting, I couldn’t help but feel let down. The Adventure of Link had actually demanded things of me, had forced me to up my game. But Ganon fell within three days that spring of ‘92. Heroism was, apparently, passé.

It’s been equally so ever since. It’s not that certain encounters or sequences in Ocarina or Twilight Princess aren’t challenging (the silent realms are a Skyward Sword highlight). But they are separate, repeatable, often asking me to merely hone a skill or discover a weak point (a strategy, they call it) before getting whacked too many times. Failure occurs, but with little penalty. And given the often incoherent controls, with little responsibility either. The games themselves, piecemeal affairs, are not difficult. It’s never a matter of if I’ll succeed, only when.

Don’t get me wrong: modern Zeldas are not simple, only simpleminded. Some of this comes from convention and repetition, both within and across games. The path through each is laid down with paternal care. One senses at every turn that the experience has been carefully crafted by someone who surely knows best. His guiding hand remains on the gameflow spigot so that it drips steadily; meanwhile, you won’t be tempted to get ahead of yourself or go out of order. The first time you play Zelda, it’s no surprise that this tasteful staggering of content and gentle guidance of the player comes off as masterful game design.

For veteran players like myself, though, the profound conservatism at Zelda’s heart feels more patronizing with each repetition. Why bother paying attention to the old man when I can just tune out and coast? The game will do all the fretting for me. It won’t let me fail. I don’t even have to get good; I just have to get through. Zelda asks nothing, demands nothing, except that I play along.

Another way to say this: modern Zeldas do not respect the player. Many gamers express this as too much handholding and blame the Nintendo helpline reps who accompany you through Hyrule. No doubt, Navi, Midna, and Fi intrude, remind, and overexplain, all naggy and mothersome. At least Midna, one of the only strong characters the series has yet to produce, is cheeky when she chastises you. Yet even if these more obvious guiding hands were eliminated from Zelda, respect for the player would not be restored. Each game is one giant guiding hand, and even when its condescension is not spelled out very slowly via text scrawl, its gated world, blatant signaling (this goes there), and countless safety nets make sure the player gets the message.

Some contend that all of this is really for the new kids and we longtime Zelda players (the actual fan base) just have to suffer along like patient older brothers and sisters. If only anyone could convince me that the tangled conventions that define Zelda were also approached with new players in mind. Zelda pretty clearly wants to have it both ways, but it’s hard to imagine either veterans or novices being satisfied with, say, Skyward Sword. Every Zelda has to be someone’s first, but I can’t help pity the player who thinks this is what the legend was all about.

Actually, we needn’t speculate on what the gods of Zelda had in mind when designing the difficulty. Eiji Aonuma, director of Zelda since Ocarina, spoke to Game Informer about this directly:

“I never actually finished [the original Legend of Zelda]…I almost feel like there’s still no game more difficult than it. Every time I try to play it I end up getting ‘Game Over’ a few too many times and giving up partway through. Certainly after playing the original Zelda for the first time, I didn’t ever think that I wanted to make a game like that.”

Congratulations, Mr. Aonuma – you never have. Instead, you’ve taken the teeth out of a hardcore series. There’s no real danger now, no risk, nothing to lose. You’ve redefined game designers as the ultimate helicopter parents.

The point of a hero’s adventure (and Zelda is the hero’s adventure in gaming) is not to make you feel better about yourself. The point is to grow, to overcome, to in some way actually become better. If a legendary quest has no substantial challenge, if it asks nothing of you except that you jump through the hoops it so carefully lays out for you, then the very legend is unworthy of being told, and retold. Death and punishment for failure are not outdated old-school notions, too demanding for the new eggshell generation. Nor are they too grim for the charm and wonder essential to Zelda’s tone (Mario proves you can be both delightfully whimsical and motherfucking hard). Meaningful difficulty, in which successes are owned and failures chastise rather than annoy, would more deeply engage the player, making her responsible, necessary, worthy of the legend. Not just the recipient of a gold star, the kind you get for showing up.

Death Mountain Speaks for Itself

Zelda would be better if it had no story. Or more precisely, no plot to structure the adventure. The first Zeldas barely had any plot, and they were the better for it. With plot, sequence matters too much. The early Zeldas had situations, worlds and scenarios that framed the action, gaps to be filled in by the player, sequences to be broken. Optimal paths and shortcuts weren’t a given; they had to be earned. Items were the most prominent plot devices, and even they were not unduly strict about order. You could be slow and steady or blast straight through with a little know-how. The basic rules of the gameworld were what bound you, not some artificial necessity imposed for the sake of plot. You could even play through the entire first Zelda up to Ganon without ever getting a sword.

Plot in modern Zeldas is another culprit in the Case of the Sluggish Pacing. It only thinly veils the mechanics being explored, and it bends the adventure in ways that feel forced and unnatural. Especially when the needy denizens of Hyrule get involved. At this point, I fear speaking to anyone without a golden triangle on her hand. When did everyone become so inane and needy? The original Zelda had no villages or houses; the only remaining residents were hidden away in caves, the clearest indication that Hyrule had already fallen to the enemy. They were cryptic, terse, mercenary and only rarely asked anything of you (one letter to be delivered to an old woman, one grumbly Moblin to be fed). Link was a student of Hyrule and its people, learning how everything worked, how the world could be saved. He was not the people’s personal benefactor slash errand boy. This makes the player feel awkwardly like both the center of the universe and an indentured servant. Myself, I need neither additional chores nor reinforcement for my solipsism.

Zelda doesn’t even have central characters. It has echoes. Repetitions with variation. Only one-off characters, like Midna, have a singularity that matters. The rest are foregone conclusions. At their best, they can offer nuance or temporary affect, but the very nature of Zelda’s iterative narrative makes it hard for anything to stick. Even the more vibrant versions of characters (Wind Waker’s Tetra, Skyward Sword’s Zelda) are hamstrung by the larger narrative’s conservatism. Get your crown on, princess. Go to sleep.

Building up a world with a past, a believable place with its own logic – that would be enough. Wind Waker’s post-apocalyptic drowned world was enough; Majora’s Mask’s temporal loops and grinning lunar horror were enough. Zelda is a perfect candidate for environmental storytelling. A Hyrule you can dwell in, despite its limitations (perhaps because of them), with gameplay that compels you further in – such a world will produce its own stories. It will speak without over-signaling, it will invite readings without being immediately legible, it will become evocative, a space to be occupied by imagination. A place of wonder.

To do this, Hyrule must become more indifferent to the player. It must aspire to ignore Link. Zelda has so far resisted the urge to lavish choice on the player and respond to his every whim, but it follows a similar spirit of indulgence in its loving details, its carefully crafted adventure that reeks of quality and just-for-you-ness. But a world is not for you. A world needs a substance, an independence, a sense that it doesn’t just disappear when you turn around (even if it kinda does). It needs architecture, not level design with themed wallpaper, and environments with their own ecosystems (which were doing just fine before you showed up). Every location can’t be plagued with false crises only you can solve, grist for the storymill.

Some Zelda critics complain about padding and filler, especially in Skyward Sword. But Zelda’s plots have long been game-length filler, filling in for a failed, unbelievable world. Its clockwork vistas do not evoke stories, so it must construct plots to tell them. The game mechanics of early Zeldas provided plot enough, the kind that is boring to tell (then this, then this) but thrilling to play. They required no narrative scaffolding to be justified; they justified themselves. And strangely, the iconic simplicity of early Hyrules fired the imagination the way a good map does, opening up story possibilities rather than narrowing them down to just one. Story flowed from world instead of world from story.

Zelda II performed a masterstroke in sequel-land when, after handing you your ass in the Death Mountain maze, it revealed the world from the first game to be but the tip of the Hyrulian iceberg. It altered the scale of the screen (the original overworld’s 128 became approximately 1) and thus expanded the scope of the entire adventure in the player’s mind. The raised stakes of the sequel were palpable; they were right there on screen. The world, not the towns or their people or any text, grounded the adventure, gave it shape. Death Mountain spoke for itself.

For all the talk of golden triangles and lost girls and pig thieves, this onscreen shift between the first two games makes visible the essential Zelda story. It’s the movement from the world you know to the one beyond, from country to city, from country to world, ongoing still, ever incomplete. It never gets old because it speaks to the inexhaustible experience of growing older, the perpetual Katamari Damacy scale shift of a life in time. Modern Zeldas don’t need to lean on tired plots to tell this story. The player could experience it firsthand if offered a compelling, expansive Hyrule, the kind of world that seems to expand the more you explore it.

Old Zelda Hands

There’s nothing like your first time, I know. For players who came to Zelda later than me, I’m aware my criticism is treading on sacred ground. But unless Twilight Princess or Skyward Sword was your first, the rest of the Zelda faithful must at least recognize the limits of the formula and how little the core experience ever changes. For me, being a Zelda fan means wanting each new game to be the best possible Zelda, to further its promise as a videogame.

So fans can both acknowledge that a series’ glory days are long past and still earnestly hope that they’re wrong with each new release. The revival of a once-great series also does not entail a simple return to its roots. Despite all that modern Zeldas might learn from the first two, I’m not advocating remakes or revivals. 3D Dot Game Heroes tried this with Link to the Past as its model, and the result was curious for a few hours but ultimately slavish and unfulfilling, like most nostalgia projects.

Yet belief in Zelda is not based simply in childish attachment or blind need. There is really some magic there; Zelda has not survived so long by chance. The pleasures it first offered – those that come with being an explorer, a pathfinder and labyrinth conqueror, a fighter and survivor, a finder of secrets – remain completely viable in modern games. They’re just not present in modern Zeldas. Instead, we are given an unconvincing world, unfocused gameplay, unsatisfying difficulty, and an unnecessary story. Skyward Sword is guilty of all of this and more, and yet as the proclaimed future direction of the series, it is unapologetic. This is Zelda, they say, and you can hardly remember a time when it was much different.

But I remember. I remember the peerless original, its unfairly-maligned sequel, and those later elements that suggested the magic had not been completely exhausted, from Wind Waker’s exuberant charm and grace to little Midna’s boundless sass. Yet focusing on the series’ greatest moments won’t save Zelda. Its obsession with its own conventions and culture has resulted in an insular little kingdom, walled off from the rest of gaming. Zelda no longer has a vision of anything but itself, and the wrong parts at that. It is choking on its own tail.

If I were to suggest where else Zelda might look for inspiration, it wouldn’t have to go far. Mario remains as vibrant as ever, in no need of saving. No series has so many extraordinary, crucial games that still sing when you play them. Its focus on jumping and all its variations is bold and visionary rather than conservative and safe, and it manages to make the familiar new again and again. As a model for how to develop a series, you could hardly do better than Mario. But that would still not help create a single new Zelda, encumbered by its own legend as it now is.

For a while, I’ve been unable to imagine a better Zelda myself, not even as a reboot with a new studio. I sensed what was wrong, and yet I couldn’t point to another modern game that offered many of those original Zelda pleasures. Then I played Demon’s Souls last fall. Its unremittingly bleak vision would seem to have little to offer a land as enchanting as Hyrule. And yet, it captured my imagination (claws sunk into my brain, to be more precise) in a way that few have since the original Legend of Zelda. Its world seemed real, lived-in (died-in), with a history and an artistry that burned every twisting passage into my memory. Its gameplay was focused, coherent, and deep, built around encounters that were far more intellectual than Zelda’s puzzles. Its famous difficulty demanded so much, not just from my hands but from my entire ragged nervous system, even from my temper, my character. It never explained itself and so conjured, via ingenious online components, a community as helpful and treacherous as any group of humans. And yet its difficulty was also exquisitely balanced and eminently fair. It respected me enough to let me fail, then gave me reasons to try again. And it graciously pushed all of its storytelling into the background, letting the world speak for itself.

After Demon’s Souls, I felt a better Zelda was possible. The core experience it offered had not become obsolete over the console generations after all. Games were still capable of possessing me; I was still capable of being possessed. This didn’t mean another great Zelda would necessarily be like Demon’s Souls, especially in structure or tone. But its spirit might be saved, so that old Zelda hands like myself might dream of Hyrule, and its secrets, again. Isn’t that what we want? For games to get deep inside of us, to restructure our consciousness, to reroute our labyrinthine nerves, to resonate with our captive hearts, to matter? The way legends do.

~ Tevis Thompson

Published February 10th, 2012

Note: This essay has a Second Quest, a graphic novel with artist David Hellman.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.