Thunder Force III and Trance

First person description alone won’t capture the trance experience of Thunder Force III. Shootshootshootshoot (holding B) up and back then wait til NOW and forward to FLOAT. Switch weapons. We’re getting nowhere.

First person description alone won’t capture the trance experience of Thunder Force III. Shootshootshootshoot (holding B) up and back then wait til NOW and forward to FLOAT. Switch weapons. We’re getting nowhere.

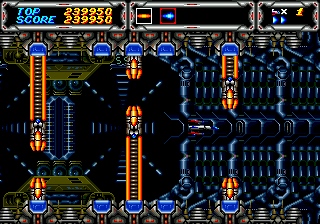

I’m not just the ship, even if I control it directly – I am the whole screen, scrolling forward. To play a shooter like Thunder Force III is to master everything on screen at once, an overwhelming encounter with numbers and speed and geometry, an exercise in graphic discrimination (what is what). It is to constantly prioritize danger, which to kill first. To optimize weapons and memorize the entry points of threats, the weak points of bosses, the shifting safe zones. To sync with the game’s rhythm.

And to master the ship – my armed and elastic core. Each weapon extends its reach, its range of efficacy. As such, I feel my phenomenal field, the very horizons of my virtual body onscreen, fold and deform with each bullet I release.

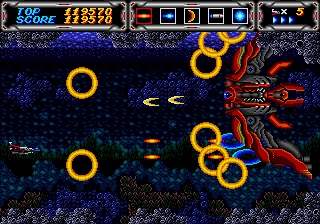

The basic double shot I start with provides a steady horizontal rain (because I rarely stop firing); this elongated tube becomes my default field of force. The other starting weapon is half as thick but bi-directional. The wave gun arcs my field out wider; missiles make it potently vertical. The hunter homes in on each enemy, lighting up the screen with threat while removing the anxiety of aiming entirely. Of course, Thunder Force III’s standard mushroom powerup – the CLAW (though some childlike ghost barks “FLOAT” when I arm it) – is an extended field itself and amplifies the range/effect of each weapon.

The basic double shot I start with provides a steady horizontal rain (because I rarely stop firing); this elongated tube becomes my default field of force. The other starting weapon is half as thick but bi-directional. The wave gun arcs my field out wider; missiles make it potently vertical. The hunter homes in on each enemy, lighting up the screen with threat while removing the anxiety of aiming entirely. Of course, Thunder Force III’s standard mushroom powerup – the CLAW (though some childlike ghost barks “FLOAT” when I arm it) – is an extended field itself and amplifies the range/effect of each weapon.

I shoot projectiles in order to project my self over the screen. I shoot constantly; there is no need to conserve bullets – they are an endless extension of myself. I don’t aim much in Thunder Force III either. I fling my bullet-limbs out and anticipate collision. I dodge, careen, and then crash my extended self into each threat. The experience of each weapon’s unique force and shape onscreen warps my very experience of presence, and vulnerability, in the game’s shifting patchwork of safe/danger zones. It is this self, this first person, upon which my eyes, ears, and hands converge to induce the trance.

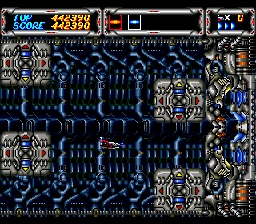

The edges of the screen delimit borders I cannot breach; to even imagine the off-screen spaces (at least those that are not eventually scrolled over) seems unnatural, like trying to look past the edge of the universe, or a Monopoly board. How easily my mind accepts the limits that define Thunder Force III’s gamespace.

The edges of the screen delimit borders I cannot breach; to even imagine the off-screen spaces (at least those that are not eventually scrolled over) seems unnatural, like trying to look past the edge of the universe, or a Monopoly board. How easily my mind accepts the limits that define Thunder Force III’s gamespace.

Within its borders I encounter elemental themes, as in so many other videogames. There’s something pure, almost platonic, about a world of ice or fire. The best of such levels provide a meditation on the fundamental constituents of our universe, the fine particles of our experience. They create a spatial elaboration of some of the rawest categories of our mind. Air and earth, metal and wood, even distilled landscapes: forest, desert, mountain, sea (the monomaniacal ecosystems of George Lucas’s planets never bothered me). Human products too – toys, sweets, machines – can take on a mythic weight when properly thematized as a videogame level.

Thunder Force III elaborates its variations on two-dimensional space via standard elemental themes. The layered foliage of Hydra trains my eyes to discriminate background from biomechanical foe while scrolling itself out simple and straight. The mesmerizing fire waves of Gorgon (probably the most memorable aspect of the game decades later) intensify the visual task while enclosing my field further with igneous intrusions and vertical lava bars. The bubbles of the oceanic Seiren stage effect a kind of reverse gravity, and the subterranean halls of Haides constantly shift, making the environment itself the greatest threat. At times, my ship’s field is reduced to a tiny pocket as I stall between crags. This earthy level perhaps best literalizes the shifting zones I must constantly feel out and negotiate to keep playing.

Thunder Force III elaborates its variations on two-dimensional space via standard elemental themes. The layered foliage of Hydra trains my eyes to discriminate background from biomechanical foe while scrolling itself out simple and straight. The mesmerizing fire waves of Gorgon (probably the most memorable aspect of the game decades later) intensify the visual task while enclosing my field further with igneous intrusions and vertical lava bars. The bubbles of the oceanic Seiren stage effect a kind of reverse gravity, and the subterranean halls of Haides constantly shift, making the environment itself the greatest threat. At times, my ship’s field is reduced to a tiny pocket as I stall between crags. This earthy level perhaps best literalizes the shifting zones I must constantly feel out and negotiate to keep playing.

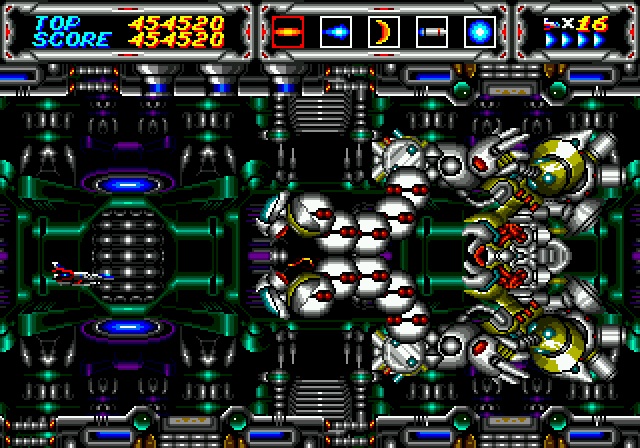

Rimy Ellis adds diagonal and vertical scrolling. This strangely generates the feeling that it is not my ship moving at all, but the landscape which momentarily enfolds me before moving on. This illusion of movement is further spoiled by the elaborate final stages – the roundabout assault on the Cerebus spaceship and the interior maze in the guts of Orn. The more tricks Thunder Force III pulls, the more directions I am pulled, the less movement I feel. At this height, or depth, or breadth of play, I see a flat screen, a rectangular universe that doesn’t move at all.

And I am centered there. Not in the center of the screen, but on the screen itself as center and circumference of my scrolling self. This is not just absorption; most decent games can pull that off. This is synchronization, nearly unconscious, flirting with automation.

It helps that 2D shooters tend so easily towards abstraction. The flat gamespace, fixed perspective, and restricted movement, along with the often strong color contrasts and bold shapes, must activate some basic circuitry in my lizard brain. By alleviating both the need for 3D processing and the burden of exploration, I am free to engage my primal perception toward a single end: survival, not just that of my ship but of the trance I wish to sustain.

It helps that 2D shooters tend so easily towards abstraction. The flat gamespace, fixed perspective, and restricted movement, along with the often strong color contrasts and bold shapes, must activate some basic circuitry in my lizard brain. By alleviating both the need for 3D processing and the burden of exploration, I am free to engage my primal perception toward a single end: survival, not just that of my ship but of the trance I wish to sustain.

This requires a kind of untraining of my brain. I must turn off my everyday perception, so concerned with depth and perspective, and think two-dimensionally. I must ignore the illusion of movement and the false depth of parallax scrolling. It is not unlike the training which asks the artist to flatten the world and see only its lines and shapes, to short-circuit the usual collating of distance and perspective in the brain, the 3D worlding it executes so relentlessly. I must see only light on a surface, and I must linger there.

The aural elements that require syncing for the full trance effect have, perhaps, a more direct line to my autonomic nervous system. The power rock soundtrack as piped through the Sega Genesis may be tinny and thin, but this doesn’t diminish its hypnotic power. The rolling keyboard crescendo of Seiren and warped melody line that echoes through Haides benefit from its hard, wiry sound. Repeated play and expertise can even lead me to prefer guns based on their sound. The shrill sonic warble of the wave beam or harsh keening of the lancer can become unbearable over time, and I find myself returning to the light pitterpatter of my original doubleshot.

The aural elements that require syncing for the full trance effect have, perhaps, a more direct line to my autonomic nervous system. The power rock soundtrack as piped through the Sega Genesis may be tinny and thin, but this doesn’t diminish its hypnotic power. The rolling keyboard crescendo of Seiren and warped melody line that echoes through Haides benefit from its hard, wiry sound. Repeated play and expertise can even lead me to prefer guns based on their sound. The shrill sonic warble of the wave beam or harsh keening of the lancer can become unbearable over time, and I find myself returning to the light pitterpatter of my original doubleshot.

The forced scrolling syncs with the music to create a unified audiovisual landscape, such that every enemy entrance and movement is exactly cued to the soundtrack. The only potential hiccup comes with the entrance of mini-bosses, and this curiously creates another incentive to kill them by the quickest, most efficient, most repeatable method possible, so as not to get off track. Failure to dispatch mini-bosses the same way every time punishes the player with a remaining level in which the music is subtly out of kilter.

Higher levels of difficulty require the player to revise the cues for this two-dimensional dance. What were once empty areas for down time on the normal setting become filled with additional bluster and threat at the ‘hard’ and ‘mania’ levels. Choosing a difficulty is thus also a selection of landscape density, of how much breathing room you want in each level. Accordingly, a more skilled player can hold her breath longer.

Higher levels of difficulty require the player to revise the cues for this two-dimensional dance. What were once empty areas for down time on the normal setting become filled with additional bluster and threat at the ‘hard’ and ‘mania’ levels. Choosing a difficulty is thus also a selection of landscape density, of how much breathing room you want in each level. Accordingly, a more skilled player can hold her breath longer.

Thunder Force III’s seven main levels each last about the 3-4 minutes of an average pop song. All together, a complete play-through (without dying and continuing) comes in under 30 minutes, the length of a short album, or long EP. And like the attention and concentration we used to give those musical artifacts, a focused play-through can be similarly meditative and centering.

I hold one button continually (to fire), tap another on occasion (to switch weapons), hit the last one a handful of times (for speed changes). Firing my weapon and extending myself across the screen requires mere steadiness. Weapon selection is a matter of evaluating the present threat and predicting/remembering the future. Speed is only adjusted for the momentary tight squeeze.

Thunder Force III is really a game of joysticks (or directional pads). As with so many of its forerunners, simple movement is primary. (Early gamers just couldn’t DO much with buttons, their verb-set about as wide as that of an American tourist abroad.) So I hold the balled end of the joystick with my fingertips. I push and pull fluidly in each direction and feel the one-to-one correspondence between my bearing and the ship’s. There is some minor thrill in the translation of small hand gestures to magnified movement onscreen. I constantly adjust, centering and recentering the tender locus of my energy, the fount from which my bullets spill forth. The joystick itself resists me with its own recentering, and when I change the nominal speed setting of my ship, what I’m actually doing is recalibrating joystick sensitivity.

Thunder Force III is really a game of joysticks (or directional pads). As with so many of its forerunners, simple movement is primary. (Early gamers just couldn’t DO much with buttons, their verb-set about as wide as that of an American tourist abroad.) So I hold the balled end of the joystick with my fingertips. I push and pull fluidly in each direction and feel the one-to-one correspondence between my bearing and the ship’s. There is some minor thrill in the translation of small hand gestures to magnified movement onscreen. I constantly adjust, centering and recentering the tender locus of my energy, the fount from which my bullets spill forth. The joystick itself resists me with its own recentering, and when I change the nominal speed setting of my ship, what I’m actually doing is recalibrating joystick sensitivity.

These are basic components for establishing a typical videogame feedback loop, but closing that loop and dwelling there is the trick. I’m not just trying to fuse biological me with a mechanical system – to get my cyborg on, as it were. I’m trying to merge the virtual onscreen with that of my mind, to collapse the distinction, to access the machine that is me. Doing this successfully induces the trance.

Trance: the word is ambiguous. A trance state is half-conscious, cut off from the world outside its narrow focus. Zombies, automatons, the possessed come to mind. The repetition and isolation from the human world unnerve the observer. But there are other images as well: the artist immersed in her work, the skilled mechanic or pianist, the visionary and his visions. Even the ‘flow’ of so much positive psychology lines up well with the trance state.

Trance: the word is ambiguous. A trance state is half-conscious, cut off from the world outside its narrow focus. Zombies, automatons, the possessed come to mind. The repetition and isolation from the human world unnerve the observer. But there are other images as well: the artist immersed in her work, the skilled mechanic or pianist, the visionary and his visions. Even the ‘flow’ of so much positive psychology lines up well with the trance state.

But where is the entranced gamer amidst all this? Is she mindless or mindful? And what about afterwards? Is she energized, fulfilled, renewed or guilty and empty? The inconsistency still plagues gamers. Even as I describe my positive experience with Thunder Force III, I want to preserve the ambiguity of the videogame trance. Because its character and effects depend on both the particular game and the individual player. All clamoring for objectivity aside, it is a person who must ultimately interface to produce the actual game experience. Videogames do not generally play themselves.

For me, Thunder Force III creates a vibration. Something humming or buzzing in my skull. It feels primal, both animal and metaphysical, something beneath higher order absorption. The limits of two dimensions, the music and droning sound effects, the muscle memory, the rhythm of both the game and my pulse, my pulsating phenomenal field, the abstraction of myself – all of this roots me in place and binds me there, like a dream from which I cannot awake. My skills are vital because death, or even pausing, will break the spell. Twenty years ago, I needed the ‘mania’ difficulty to generate the trance; these days ‘hard’ is sufficient for my aging skillset.

For me, Thunder Force III creates a vibration. Something humming or buzzing in my skull. It feels primal, both animal and metaphysical, something beneath higher order absorption. The limits of two dimensions, the music and droning sound effects, the muscle memory, the rhythm of both the game and my pulse, my pulsating phenomenal field, the abstraction of myself – all of this roots me in place and binds me there, like a dream from which I cannot awake. My skills are vital because death, or even pausing, will break the spell. Twenty years ago, I needed the ‘mania’ difficulty to generate the trance; these days ‘hard’ is sufficient for my aging skillset.

There are limits to describing this trance. Because to truly go under is to lose my everyday self, momentarily, to lose even the senses that can be reported back. The experience is intensely present in its now, but fugitive a moment later. I have memories but something is missing, that quality of the experience which is the experience, which doesn’t cross the event horizon intact.

There’s nothing mystical about this. With repetition, it becomes a kind of ritual, and like all rituals (meditation and prayer, exercise programs, shower routines), it can open up a space for thought, for creativity, for working-through, a space to dwell within the daily. Rituals have things in common – special places, objects, movements – and these things can be virtual as well as material. With the controller and my nimble ship, the buttons and my field of force, the television screen and its two-dimensional space, I have both.

There’s nothing mystical about this. With repetition, it becomes a kind of ritual, and like all rituals (meditation and prayer, exercise programs, shower routines), it can open up a space for thought, for creativity, for working-through, a space to dwell within the daily. Rituals have things in common – special places, objects, movements – and these things can be virtual as well as material. With the controller and my nimble ship, the buttons and my field of force, the television screen and its two-dimensional space, I have both.

Seers, writers, everyday mystics try to set the conditions that will tip them into trances, fits, visions. To reach the realm of the otherworldly within. And so, what was once accidental when I played certain videogames, I now approach more purposefully. Thunder Force III’s demand of focus and skill, its reduction of three-dimensional life to two, the experience of my palpable phenomenal field within it – this subverts my ravenous, unwieldy consciousness for a solid half hour. And I emerge from the end credits, with its star field and melancholy song, strangely calm and awake.

~ Tevis Thompson

Published May 15th, 2011

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.